Literary portraits can at times suffer from the same limitations as photographic, sculpted or painted ones have.

That is, a person described can be depicted using words in many different manners, depending on the skills, the psychology and the moods of the artist, but any good portrait demands a lot from the author; indeed, not every skilled painter or sculptor is necessarily a good portraitist.

It is said that any outstanding painted portrait must take up the challenge of capturing some part of the subject’s life without the aid of the spoken or the written word.

One Dutch poet, commenting on the famous portrait of Cornelis Anslo—a renowned preacher—by Rembrandt said: “That's right, Rembrandt paints Cornelis’s voice! His visible self is a second choice. The invisible can only be known through the word. For Anslo to be seen, he must be heard”.

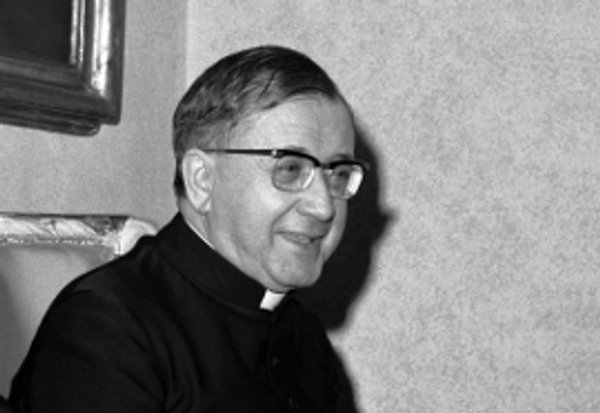

A portrait (not the portrait) of Saint Josemaria Escriva is going to be my task in these articles, contained in a series of articles.

My credentials as a painter are non-existent, but I do have some for attempting a literary portrait of the founder of Opus Dei:

I spent 22 years at his side, in Rome, from 1953 to the very day of his death on June 26, 1975. That day, as his family physician during the last years of his life, I tried to revive him after he suffered a massive heart attack in the room where I and his next two successors at the head of Opus Dei were standing. After an hour and a half of vain efforts by a small group, some of them also physicians, I closed his eyes with my fingers.

Painters make frequent use of sketches in their work. In a conventional sketch, the emphasis is usually laid on the general design and composition of the work and on its overall feeling.

Conventionally, there are three main types of functional sketches.

The first—sometimes known as a croquis—is intended to remind the artist of some scene or event he has seen and wishes to record in a more permanent form.

The second type is related to portraiture, and notes the look on a face, the turn of a head, or other physical characteristics of a prospective sitter.

The third—a pochade—is one in which he records, usually in colour, the atmospheric effects and general impressions of a landscape.

In these articles my task is going to be to present to you sketches of the first two types (the croquis and the notes I have kept in my memory since I met Saint Josemaria for the first time and during the few following years), plus a more complete portrait based on the other twenty years I worked and lived close to him.

Other writers have taken care of the pochade, describing for us the times and the historical setting of Saint Josemaria’s life and work. I mention, among others, John Coverdale, Andrés Vázquez de Prada, and Peter Berglar, who have written beautiful biographical sketches or full biographies of Saint Josemaria, the Founder of Opus Dei.

The text above first appeared in The Westbrook Voice.